What critics are getting wrong about Molly Jong-Fast's "How To Lose Your Mother"

What you're missing if you think this is a revenge memoir or if you believe Molly sold her mother out

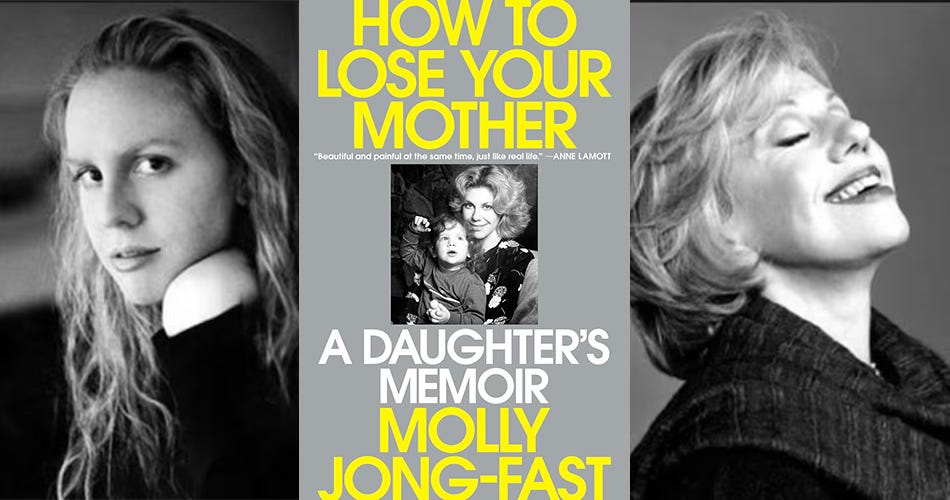

I’ve been fascinated by the response to Molly Jong-Fast’s new memoir, How to Lose Your Mother. Fascinated by the way it’s brought out the Erica Jong (author of Fear of Flying) loyalists. Fascinated by how disappointed and sad and hurt some people seem to feel that Molly wrote this memoir in the first place. That she exposed her mother in this way. Fascinated that people can read this book and see it as a revenge memoir. Like all good memoirs, How to Lose Your Mother is a prism that refracts light differently depending on how you choose to look at it: as a fan of Erica Jong’s; as a daughter; as a mother.

I loved this book. I was mesmerized by it. Then Molly was a guest on Memoir Nation, and I won’t say it was the best interview we’ve ever had, but I chalk it up to Molly having been already weary of the questions being posed to her about this book.

Over the twenty years I’ve been editing and publishing memoirs, I’ve too often seen readers level criticism against the person, not the book (especially when the memoirist is a woman, by the way). What I see in all the criticism of How to Lose Your Mother is a critique of Molly, the person. She is resentful; she is exacting revenge; she wouldn’t have even gotten this book deal if she weren’t the daughter of Erica Jong (hell, she wouldn’t even be who she is if it weren’t for Erica, that ungrateful little . . .). Underlying all of the criticism is a well-worn how dare she?

Many of the people insinuating how dare she? haven’t even read the book. They’re just upset on principle. It’s an old saw: She shouldn’t have aired the dirty laundry. But for those who have read the book and are still leveling criticism (that Molly is traumatized, poor Molly, that Molly is leveraging her mother for her own fame), they’re missing something important.

What I read in Molly’s work was a kind of irreverence. The irreverence of a woman who lived for years with an alcoholic mother who would do whatever the fuck she wanted, whenever the fuck she pleased, no matter who got hit with shrapnel as the result of her behavior and her outbursts. There’s a poignant scene in the book when Erica gives a speech at a birthday dinner for her friend Ken Follett. She writes:

It was one of those toasts in which she got hotter, and angrier, and crazier as she kept going. At some point, she got to the statement “Ken and I never fucked.” She was in her seventies. He was also in his seventies. His wife, a member of Parliament, was there too, and slack jawed in horror.

It’s true that the book doesn’t paint a pretty picture of Erica Jong. It’s also true that Molly herself is clear about what was important to Erica Jong. Erica’s career was important to Erica Jong. Erica’s fame was important to Erica Jong. Men were important to Erica Jong.

As I read this book, I thought about the people I’ve known in my life who are like Erica Jong, including my ex mother-in-law. Alcoholism is a horrible beast. It ravages lives, and anyone who’s impacted by it finds their own coping (or survival) mechanisms. Reading Molly’s book prompted me to go back and watch August: Osange County. Meryl Streep’s performance is astounding, and the movie gives insight into what it feels like to live day in and day out with a destructive addict.

In my reading of the memoir, Molly hits an impossibly brilliant tone. The aforementioned irreverence mixed with deep self-deprecation. There’s also wryness. And irony. And so much confession. It reminded me of the way a girlfriend will pull you aside at a gathering and whisper in your ear.

“In my darkest moments, I’m honest with myself. I know what I’m doing is wrong,” Molly writes about putting her parents in a nursing home. It’s startling, and the truth of it lands with an ache, but also with resonance.

About her mother, she writes:

“I want you to empathize with my mother . . . I want to make you love all of them [referring to her family], making them sympathetic characters. I want to explain to you how my mother was a deeply broken person who went from man to man trying to find an identity. I want to show you how she could not stop drinking because she was completely incapable of being honest with herself and others.”

One of my friends emailed me after she listened to How to Lose Your Mother. She expressed to me how the “profound melancholia and twisted family story rang so true that it felt oddly comforting.”

She continued with her review about Molly’s performance on the audiobook:

Jong-Fast is the literary version of Eeyore, her throat-scraping sorrowful tones becoming part of the story in and of themselves. The way she writes and the way she reads breaks every convention of advice anyone would give for producing a book that would have any commercial appeal. And my sense is, she doesn't give one single shit about that. It is not a story for everyone, and she seems intrinsically to know that too.

I’m not convinced that Molly doesn’t give a shit, but I do think there’s no amount of shame and embarrassment Molly could feel from having written and published this book that would rival the shame and embarrassment she had to swallow as the result of her own mother’s behavior.

Molly’s memoir made me think about the ways we inoculate ourselves against shame. If we get better at taking it the more it’s doled out. I’ve thought about how we compartmentalize and how we grow thicker skins. For those of us in public-facing roles of any sort, we have to. I work in a job that requires me to be out with a metaphorical bulletproof vest most days. You wouldn’t think that would be true for a publisher, but it is. Anyone with demanding clients will tell you that you have to find ways to protect yourself or you won’t survive.

But what if it’s your mother you’re protecting yourself against? And what if that woman is a nasty drunk and you’ve been many decades sober? What is the tone you’re meant to hit in your work? And what should your response be to people who tell you that you really shouldn’t have written this book in the first place because all you’re doing is shoveling trauma onto the page and selling your mother out?

There is a tenderness in Molly’s book for those who want to see it. There is heartache and longing and a deep empathy and desire to understand what made Erica the way she was, even as Molly knows she will never know. There is also heartbreak around what it looks like when an aging parent starts to lose their memory, their faculties, their very self.

Molly hardly needs me coming to her defense, but this defense is for all memoirists who are writing stories of mothers or fathers; stories of complex and toxic family life or relationships; stories of being at the whim of others and at the whim of life circumstances. The chorus of voices making Molly wrong for having written this memoir contributes to the fear of fallout that so many memoirists deal with. It’s hard enough to tell our stories, never mind to grapple with people making you bad and wrong.

The good news for Molly, I suppose, is that she owns her badness. A recurring refrain throughout the book is, I am a bad daughter. But I heard in those words a yeah, yeah, so it’s true. I’m bad, okay, so sue me. (Try this on with a New York accent and it feels a little more badass.) That’s where I saw the wryness, the honesty, the truth of being “bad” in the face of so much real bad having been done to her.

I want to say to all you brave memoirists, keep going. Writing into the truth of our experience is such a hard and courageous thing to do, particularly in the face of naysayers or inevitable fallout. Molly made me feel a little braver with my own memoir that’s stalled out explicitly because I’m worried about the other side. Memoirists like Molly light the way, and that is something to call out, and so I am.

The terror of being a memoirist, whether your mother is Erica Jong or just another mother with opinions as strong as neat bourbon and an unfortunate fearlessness about expressing them.

It takes a lot of brave & grit and guts to spill the absolute truth on the page. A lot of bleeding. It’s the writers, memoirists, like Molly who give us all the courage to step out from behind the proverbial curtain. Thank you for writing this piece. I imagine it will give more folks the courage to write their truth. Truth is messy. Messy can be mighty gorgeous.