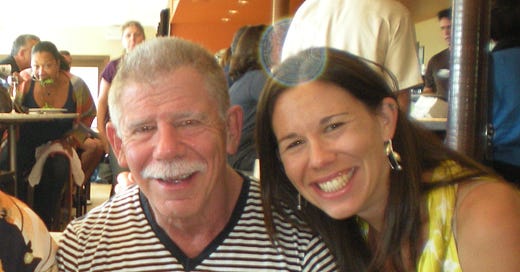

I rarely post personal work to Substack, but I’m compelled to share this today on Father’s Day in memory of my dad. I wrote this essay in March 2023 for inclusion in a someday-to-be-published collection called Grief Like Yours, which finally came out earlier this month.

My dad died two months after I wrote this, on May 15, 2023. I’m pleased to see this essay in print because I hope it might be a call to action for aging parents and their children to have the conversations we all need to have about money. My dad’s circumstances were not extraordinary—facing the end of his life with little savings, no life insurance, and the inability to support himself in the event that he couldn’t work anymore.

I end the essay speculating about how long he has left. Maybe two years, I pose. In fact, it was just a couple months. I’m still stunned by what I didn’t know, but I’m proud of us for having had the hard talks in the end while he still had a little runway left.

The Runway

“Why, Dad?” I probed, cautious of my tone, making sure the delivery was gentle and kind.

“I couldn’t see this far down the runway, I guess.”

Though my question was specific to why he’d canceled his life insurance policy, it could have been directed toward any number of financial decisions I’d been shocked to discover in the past couple weeks. A cascade of revelations had started at Thanksgiving, when he’d handed over a legal letter, postmarked March 2021—a full eight months earlier.

My dad has always been physically strong. Body builder strong. When I was growing up, he entered body building competitions and trained at Gold’s Gym in LA with Lou Ferrigno and Arnold Schwarzenegger. My friends were intimidated by him, and lots of times so was I. Even as my dad aged, his guns were impressive and his skin hugged tight to his muscles. At seventy-five, he still went to the gym every morning, as had been his routine for as long as I could remember.

Handing over the letter, he didn’t meet my eyes. The day before he’d told me somewhat cryptically that there would be no inheritance and he was sorry. I didn’t care about an inheritance per se, but I was confused. “But you have the condo,” I said. I knew he’d bought his home in 2000 for $250,000; surely twenty-one years later he owned it nearly outright.

“I think I messed up,” he admitted.

I opened the letter gingerly and pulled out the single page, still crisp. I imagined he’d opened it and read it once, back in March. The letter informed my dad that he had until January 20, 2022, to pay $220,000 to purchase back the land his condo sat on. I looked up from what I was reading. “I don’t get it, Dad. Who is this guy, Paul Goodman?”

He spun for me the story of what had happened. He and his partner had bought their Palm Springs condominium, understanding it to be on reservation land. Then, in 2007, the local Cahuilla Indians of the Agua Caliente Indian Reservation approached the condo owners in the association with a one-time offer to buy back the land upon which these condos sat for $36,000 per parcel, a chance to own their properties outright. Nearly two-thirds of the condo-owners, many of them retirees, took the deal; the rest, my dad among them, entered into a devil’s contract. Goodman, a land developer, prescient and savvy, scooped up the parcels the owners didn’t or couldn’t purchase and set about leasing the land back to them at $187 a month, a land lease set to expire in 2036. Now, however, Goodman was retiring and passing his portfolio of properties onto his son. Fifteen years had passed since the land grab, and Goodman had apparently decided to give the owners another shot, with the asking price at seven times the original offer.

My heart sank as the details of what had transpired settled in, and even more so because I knew my dad. He wouldn’t have asked questions. He would have decided that $36,000 was a lot of money, the end. His inability to see down the runway led him to accept Goodman’s proposal, a short-term solution that effectively rendered my dad a renter in his own home.

Kicking into gear on my dad’s finances, I saw we had two options—pay the $220,000 or wait out the lease. My dad would be ninety by then, his partner eighty-three. Considering what I could already see of my dad’s deterioration in the past year, I could say with near certainty that he wouldn’t make it to ninety. He’d gotten COVID in January 2021, before the vaccine. He’d been struggling with long COVID symptoms, and 2021 had been one long precipitous decline—in cognition and memory, in fluidity of speech, in weight and muscle loss, in balance, in poor driving.

I didn’t want Goodman’s son to inherit my dad’s condo upon his passing. I saw Paul Goodman as a predator, someone who’d taken advantage of a bunch of aging condo owners in the desert, someone who understood the system and pounced because he could. His kind letter was a threat—pay me or lose everything. I wanted to strangle him.

I started with an email to Goodman, a plea to consider reducing the offer. Frankly, $220,000 seemed cruel given that these same condo owners hadn’t felt they could spring for one-sixth that amount the first time around. I poured my heart out to him, telling him the story of my father, a hard worker who’d lived a life of service. My dad, a PhD and still-working psychologist in his mid-seventies. The condo was his only asset, his security. My dad, who’d started a gay church to serve the LGBTQ community in the desert in 2008 because nothing of its kind existed. He made next to nothing on this endeavor that had been a lifeline to so many mostly gay and few lesbian congregants. People I’d spent time with. People who loved my dad, and many of whom felt he’d either saved their lives or opened back up the possibility to have a relationship with God again after all variety of family and religious traumas had been inflicted on them. My dad insisted that Jesus Christ loved them no matter what. Everyone was welcome.

None of this moved Goodman. The $220,000 number was firm, and January 20 was less than seven weeks away.

Back in the desert in January, I’d shored up a plan. We’d do a cash-out refinance loan at the advice of my CPA. Somehow the condo still carried a mortgage of $185,000, though I didn’t have it in me to ask why. But it was worth $500,000, so the refi would still keep us right-side up, though barely. At night, I lay awake fretting. My dad didn’t have the money to carry a higher mortgage, so the choice to move forward meant that I’d be covering the balance between the current mortgage and the new one.

Would it be better to just let it go, to run out the lease and kiss the condo goodbye whenever the day came that my dad passed on? I mulled over why to keep the place. It was about control and ownership; it was about decision-making in case my brother and I wanted to hold onto it as an asset, for our own use, to resell; and it was definitely about not turning over whatever inheritance this might be to Goodman’s son. I didn’t want my dad living out his final years under these strangers’ thumbs.

“He’s just a capitalist who figured out a way to make a lot of money.” This was the response of the bright-eyed loan processor handling the terms of our new bundled loan that pulled together the land and the condo into new a legal filing. She was busy adding new pages to a tower of paperwork on her desk, and it was good she couldn’t see my face behind my mask because she would have seen my lip curl up at the mention of Goodman. When she looked up at me, she must have seen my upset, though, because she stopped what she was doing and sighed. “You’re doing a good thing for your dad, honey.”

At her tenderness, the little sticks holding my heart and chest up during these weeks threatened to crack. My eyes watered and my body racked, one time only. I fought to regain composure. “Thanks,” I managed.

I asked her about the other condo owners. There had been thirteen who’d taken Goodman’s deal, and three of them were taking action like we were. The other nine would leave their land in the portfolio, passing along what was theirs to Goodman’s son.

My dad never once said an unkind thing about Goodman. He’d been nothing but honest, he reminded me on more than a few occasions. I needed a demon to blame this whole mess on, but of course, at night, while I tossed and turned over my new $800 monthly expense and the uncertainty of co-signing this loan, I blamed my dad.

How could he have been so short-sighted? How could he not have asked what his options were back then? And why did he still owe so much money on the original mortgage? More arresting, how could this man I’d believed to be so competent, my intimidating, imposing, intelligent father, be so bad with money? He’d worked his entire life. He was a PhD with a thriving practice, a minister, and yet here he was facing down the end of his life with zero financial security. He’d canceled his life insurance. His savings, I’d discovered since Thanksgiving, would last him less than one year once he couldn’t work anymore. His asset, the condo, was compromised. We were reclaiming it, but at a cost to me, and I couldn’t quantify how much my decision-making had been driven by my emotions, or know if I’d made the right choice.

My dad’s lack of financial acumen was at first stunning, and later heart-breaking. It took me months to reconcile that this had happened. Or rather, to come to terms with the fact that it had, and there was nothing to do about it. The cognitive dissonance was strong—the distance between who I thought my dad was in this arena and who he actually was broke the strong-man image I’d carried of him for my entire life. It occurred to me that he’d built an armor to cover up the vulnerabilities, and now that the dark hands from the other side had begun to reach out for him, the cracks were being exposed.

“I feel I got cheated,” he told me after we signed the loan documents, only this time he wasn’t talking about Goodman. He was telling me about his parents, my grandparents, and how they never talked to him about money. What he didn’t acknowledge was how he’d passed down to his own children this same silence.

We look to an uncertain future as my dad must close his practice soon. There will be enough money to last one year, and then we’ll face choices. I wonder whether things could have been different, had I known. Had known how willfully ignorant Dad was around money, had I known about the original offer from the Cahuilla Indian tribe, had I been entrusted with the question of whether or not to cancel the life insurance. Useless mental exercises that can be difficult to tuck away into the file folder called Acceptance.

Sometimes the image of my dad flashes to mind—that Thanksgiving day when he handed over the letter from Goodman. He was defeated, a boy in an old man’s body. He was coming clean, trusting me with something that I understood carried so much shame. He was forced into financial transparency, which revealed a lifetime of bad choices, and a mindset that suggested he believed he could defy aging, or beat back the inevitable.

I think about his runway. There’s not a lot of it left, whether my dad has two years, or five years, or ten. Our choices will be limited by decisions he made in isolation, and out of fear, and from not-knowing. I grieve for the opportunities lost, though now, with some perspective, that’s countered by the gift of what this experience has taught me. My brother and I have talked more about money in the past year than we have in our whole lives. Money and health conversations must be proactive, and in our family, at least, we’re changing the narrative from one of silence to one of openness. I will not cheat my own son out of the conversations my grandparents denied my dad. And I will not practice magical thinking because the runway is out there, waiting for all of us.

This is so powerful Brooke and it’s great to see your personal stories on here too. These conversations are so important!

This is so moving and also will be so helpful to many I suspect. Today I honor you father, along with mine.