Hybrid Huzzah

Opinion and Rebuttal to Jane Friedman's Key Book Publishing Paths, 2025-2026, from the Queen of Hybrid

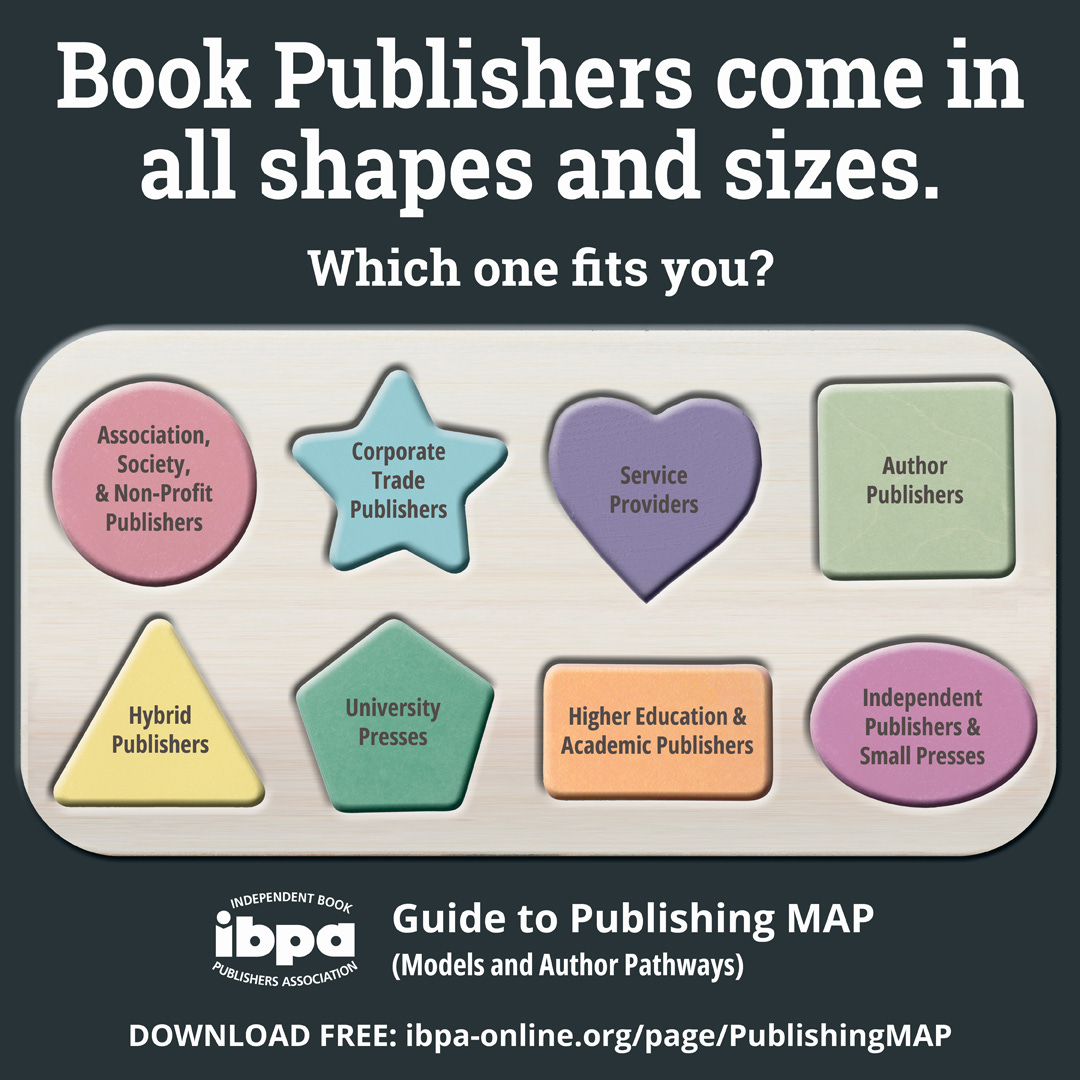

This week, fellow industry expert and industry watcher Jane Friedman (who runs the popular publishing newsletter, THE HOT SHEET) released her annual Key Book Publishing Paths update, which she’s used to chronicle the shifting publishing landscape since 2013. Notably, this year the chart expanded from one page to two, reflecting the complexities of this industry that is ever-changing and seems to want to defy categorization. The chart is a helpful resource for authors, but it’s not free from the biases of its creator. This is why I champion another important guide to publishing paths, the Independent Book Publishers Association’s Models and Author Pathways—because it was created by an association whose goal is to serve its members, and because it was created by a group of stakeholders and vetted in an open forum meeting with its members.

I call myself “publishing agnostic” because I am. I know there’s not one right path for any given author. But that doesn’t mean I’m without my biases, either, of course. I have been fighting to define and legitimize hybrid publishing since 2012. Recently, a colleague called me the “queen of hybrid,” and that’s a label I’ll wear with pride. So, with my crown affixed, and because my authors have asked my opinion about Jane’s positioning of hybrid this year, I’m using this week’s Substack post to break down my thoughts and offer a couple rebuttals.

Opinion: There is a real difference between hybrid publishing and service providers

Jane writes that “sometimes” there isn’t a difference between hybrid publishers and service providers. I argue there is, as defined in IBPA’s MAP. Hybrid publishers are and want to be your publisher; service providers are not attempting to be the publisher of record for their author clients.

Advice: There’s a tool for vetting hybrid publishers

I appreciate the caveat from Jane’s chart that reads: “Some services call themselves ‘hybrid’ when they are not a hybrid.” This is an essential thing for authors to understand. Most of the fraught energy around hybrid stems not from the hybrid publishers that are doing good work in the world, but from predatory companies using the label of hybrid when they’re not. When I first started She Writes Press, the term “hybrid” didn’t exist. There was co-publishing and there was partnership publishing. We were casting about for a word that made sense for what we were trying to do. The only other hybrid company I knew of was Greenleaf, and even they hadn’t adopted the term “hybrid” yet. Then, hybrid got popular. Or rather, it became destigmatized because of the good work of early hybrid pioneers. And all of a sudden, a flood of companies entered the marketplace, with all variation of quality, offerings, and contracts. I have been watching this from the sidelines for more than a decade now—and it’s the Wild West—then and now. If you’re an author considering hybrid, please use the IBPA’s Hybrid Publisher Criteria Checklist, which was created explicitly to support authors and the industry to be able to vet hybrid publishers.

Rebuttal: Hybrid publishing is “leveling up” from self-publishing

Jane’s chart reads: “The biggest mistake authors make in looking for a hybrid publisher is believing a ‘hybrid’ will be a ‘level up’ from self-publishing.” Here’s where Jane and I diverge. I will speak from my experience as person who spent 9 years in traditional publishing, 13 years running a hybrid publishing company, and who’s supported hundreds of authors to self-publish over the years. If you are working with a legitimate hybrid publisher with traditional distribution, your book will absolutely do better than if you self-publish. She Writes Press’s raison d'être is to “level the playing field.” For authors who can’t get traditional deals (or who opt out), the only way to level the playing field is through distribution. There are a handful of self-published authors who have the savvy and capacity (and built-in audience) to move and sell inventory, but authors who are drawn to hybrid publishing do not want to be in the business of publishing. They want the expertise and the infrastructure and the inventory storage and management and the sales and distribution efforts of a publishing partner. When I worked at Seal Press, we had books on our list that never broke 500 sales. We had other books that surpassed the tens of thousands. The same is true for She Writes Press. When you have a list of hundreds (or thousands) of authors, some will perform well, some won’t. The issue is that traditional publishers don’t bear the brunt of author disappointment in the same way hybrids do because traditional publishers cover the expenses. You can’t really complain (loudly, at least) about your sales results if someone else paid your way. Hybrid publishers are just like any other publisher—we have hits and misses, but to suggest that it’s not a level up from self-publishing is to seriously mischaracterize what hybrid publishers with deep publishing expertise and traditional distribution are doing for their authors. If all hybrid publishers did was expensive self-publishing, this particular path to publishing would have been dead on arrival years ago. The proof is in the sales . . . and those are measurable.

Rebuttal: Hybrid was and still is innovative

Jane’s chart goes on to say: “Authors biggest mistake authors make in looking for a hybrid publisher is believing . . . that it’s more ‘innovative’ than traditional paths.” In 2017, She Writes Press won a prestigious award—the Book Industry Study Group’s Innovator award. Nine years later, I’m still trying to be innovative. For me, innovation is about creating new opportunities and better offerings for my authors. Hybrid publishers have more flexibility than traditional publishers because we’re smaller, and we can be more creative, and we’re not locked into some of the complex decision-making and straightjacketing that makes traditional publishing so risk-averse. I would venture to guess that Jane believes that “innovation” is a sticky concept when it comes to publishing in general, and I agree. Any new publishing model that comes on the scene is “innovative,” and the hype can feel a bit—hyperbolic. It happened with Zibby Publishing; it happened more recently with Authors Equity. But usually it’s other people calling us innovative, or calling us disruptors. We’re not ringing the bell of our own innovation so much as people are looking for stories, and looking to qualify the Wild West. And when I look back from now and consider what’s happened in publishing since I started She Writes Press, I do think that hybrid publishers managing to wrangle—and earn—their way to legitimacy is pretty fucking innovative, actually.

Opinion: Yes, companies play to authors’ egos, so beware

Also from the caveat section of the chart, Jane mentions that hybrids and/or service providers will play to authors’ egos. I completely agree, and think authors need to be very very careful. Recently, an author who wants to publish with She Writes Press told me that another hybrid accepted her manuscript as is, and loved it so much and said they wouldn’t change a thing, whereas we were telling her the manuscript needed significant development work. She asked me why she should go with us when the other publisher was telling her the book was good to go. I marked up 50 pages of her manuscript to show her what I thought the issues were—and she agreed. Her book is now in development, and presuming we whip it into shape, we’ll offer her a contract. Flattery will get authors nowhere. A hybrid publisher can’t and won’t last if they publish work that’s not ready for prime time. You can publish some lesser-quality books and get away with it, but not consistently over time. You can’t build a reputation, a backlist, or strong sales by publishing books that aren’t ready. So, I agree, and the best hybrid publishers I know are vetting like crazy. Our vetting practices have gotten stricter and stricter over the years. This matters because publishers, not readers, should be the ones vetting authors’ work.

Opinion: Traditional publishing—is it broken? Yes.

I read Jane’s work enough to know that she strongly dislikes the messaging that traditional publishing is broken, which is why she mentions in her chart the notion that companies will “harp on how traditional publishing is broken.” I’ve been a person who’s written about traditional publishing being broken over the years. It’s the subject of my TEDx talk, and I come out of traditional publishing, so I witnessed a very real break firsthand—when Seal Press got acquired by The Perseus Book Group, and later by Hachette, which was around the time this feminist press got a male publisher and lost a certain something as a result. I harp on traditional publishing being broken because I’m living it. What I see is traditional publishing: 1) chasing trends; 2) relying on authors’ platforms to justify the acquisition of a given book (meaning it’s near impossible to get a book deal without a platform or following); 3) being ageist; 4) being overly risk averse; 5) spending a lot of money for an acquisition and then not back it up with publicity and marketing dollars; and more . . . Does this mean that hybrid, by comparison, is perfect? God no. But hybrid publishers talk about traditional publishing being broken because a lot of authors who choose to go hybrid have had experiences with traditional publishing that have left them feeling like shit. Some have previously published traditionally; some have been rejected for reasons that have nothing to do with the quality of their books; some have been met with the glossed-over gaze of an agent at a writers’ conference who will say something as sweeping as, “Memoir doesn’t sell.” I’ve witnessed all of this time and time again. Every week I talk to authors and hear their stories. So yes, traditional publishing has problems. If it didn’t, though, there wouldn’t be room for all these other creative models. So God bless.

Closing fun fact: Hybrid has bestsellers

This part isn’t on Jane’s chart, but I want to give a shoutout to my friends at Collective Book Studio and Forefront Books, both hybrid publishers (though CBS’s model is nuanced) with distribution from Simon & Schuster that had New York Times bestsellers in 2024. This is no small thing, and speaks to the power of hybrid and bigger-name authors choosing this path, and to the power of distribution. Had Taylor Swift hybrid published instead of self-published, she would not have run into the massive problems she experienced with her Eras Tour book, and she still could have retained the kind of control she was undoubtedly seeking by keeping it all under her own empire. She wanted to do it her own way, but what she didn’t know about book publishing shows why you want to partner with experts—even if you have one of the biggest platforms in the world.

The upshot here is that publishing is keeping us on our toes, and hybrid is a business model worth championing. What hybrid has managed to do in the past decade is nothing short of astonishing, and I’ll be out here fighting the fight—which for me is all about supporting my authors, creating the best books we can make, and continuing to innovate by finding and figuring out opportunities that increase visibility and sales. Which pretty much sums up the job of being a publisher.

Onward.

Brava. There is no single right path in publishing. SWP’s publishing my three (soon to be four) books helped me get on with my writing life. Such a great learning, growing experience, connecting with readers. So much better, for me, than hanging back like a wallflower at a high school dance, yearning to be chosen. I’d rather just get out there and dance. Just dance.

Brilliant glorious rockstar you! To misquote Stevie Nicks, you make writing fun.