I just finished Amanda Knox’s Free (she’ll be on our podcast in May—very excited). I love this book. Dare I say it’s a necessary book for our times. Every day I’m struck by how divisive this era we’re living in is. I can’t remember a time in my life when I felt such a swirl of exasperation and fear and disappointment and anger. We’re ratcheted up—with very few people modeling how to lower the temperature, or how to see the humanity in the people who’ve hurt you, who’ve disappointed you, who don’t believe what you believe.

I relate so much to Amanda Knox for her ability to see multiple sides of a situation, even gruelingly challenging ones. I relate because I’ve never been overly rigid in my stances or my beliefs. I’m forgiving. I seem to be prewired to be conciliatory—and capacious, meaning that I make room for what others bring to the table. Which is how I can have a friend who voted for Trump and an anti-Zionist friend, even when their beliefs are at odds with my own. I’ll go to great lengths to make room for the people I love, and yet, things have never felt more tenuous than they do now. And I’ve never seen so much relationship rupture as I have in our modern political moment.

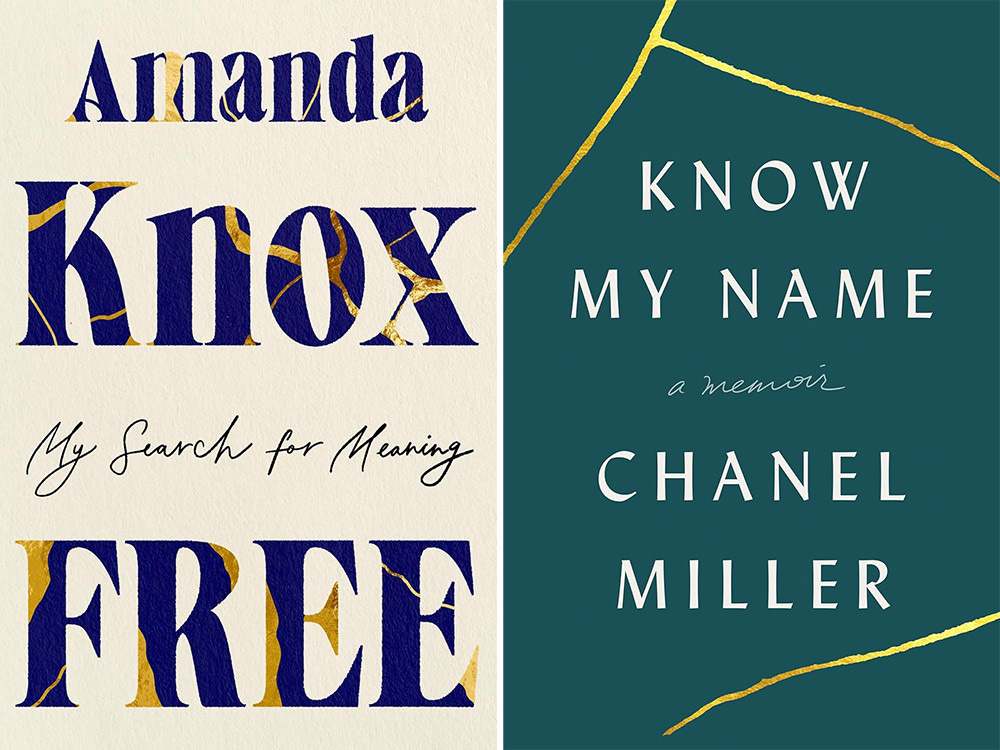

This is part of why Free spoke to me so deeply. Amanda Knox suffered great harm, and at the heart of this book is her quest to repair by reaching out to her prosecutor, the man responsible for her conviction, and responsible for demonizing her and ruining her reputation (and her life). Like Chanel Miller’s book, Know My Name, the cover art of Free uses as its primary visual element the Japanese are of kintsugi—a representation of the art (and beauty) of repair.

We have so few models of repair in our society right now. Our administration’s symbol of strength and change is a literal chainsaw. It’s hard to imagine something being in deeper contrast to kintsugi than that.

It was poignant timing for me, in the midst of reading Free and considering the value of repair, to have dinner with Gina Frangello last week. (We’re both spending a lot of time in the desert these days and we got together in glorious Palm Springs.) My connection to Gina grew out of an act of repair, an experience that stands out as one of the most important growth moments of my adult life.

The short version of the incident is this: Dani Shapiro wrote a scathing review in the New York Times of Gina Frangello’s memoir, Blow Your House Down. She called it rage-fueled, suggesting it was a revenge memoir. Unconsciously, and I might add self-righteously, I publicly praised Dani Shapiro’s review on Facebook. I dismissed Blow Your House Down as being the kind of book that sought to settle scores. Problem was, I hadn’t read the book.

What followed was humbling. What followed also speaks volumes to the kind of human being Gina Frangello is. Countless comments flooded my feed, many in defense of Gina, in defense of Blow Your House Down. People asked me very directly, Have you read the book?

Over the next days, I devoured Blow Your House Down. I count it among my favorite memoirs. It is not rage-fueled. It’s an exquisite example of how to write about being harmed and doing harm. It’s so very human, and courageous, too, in that Gina doesn’t shy away from showing us her flaws. In fact, quite the opposite, she holds her own foibles and sins up to the light for examination, for judgment, and begs us to grapple with the situations we find ourselves in, and the choices we make.

I posted a public apology to Gina—which was scary, but important. It was a act of repair. I owed it to her, and I needed to do it for myself. What ensued? Gina reached out to me. We had many conversations after that. I interviewed her for a series called WomenLit. She taught a memoir class for a series I cohost. She became a friend.

Things could have gone another way. Gina could have seen the apology and balked. She could have felt it wasn’t enough, or too little too late. She could have been closed off, unmoved. She could have decided I was a terrible person for being so ignorant and blind in the first place and not reached out to acknowledge my apology, and I wouldn’t have been any the wiser. We both would have carried on.

In Free, Amanda Knox seeks an apology from her prosecutor, Giuliano Magnini, that she never gets. About apology, she writes:

[T]rue apologies are specific and without excuse; everything you say before “but” doesn’t count; we are what we do and how we act; it is tragically easy to cause tremendous harm while believing we are doing the right thing; when we feel righteous, that’s when we must be most humble and self-aware.

There are many more profound insights to glean, so read the book. Please, read the book. The work of repair of course requires that both sides be open to conversation, and be desirous of reconciliation, even if and when they don’t get exactly what they want. Here is perhaps our biggest challenge politically right now. There is so much self-righteousness, and so little humility and self-awareness.

Amanda Knox writes of kindness throughout her book, sometimes in a way that made me feel like she’s coaching herself to be kind, to stay kind. And I think at times that’s a true articulation of what it takes to extend an olive branch, to overcome our own frustrations and disappointments when we want people to be better. And yet, “to be better” in itself is a subjective measuring stick. Gina might have shut me off because of my uninformed hurtful comment; Amanda Knox would have been beyond justified in cutting Mignini loose after his inability to apologize for what he did to her; any one of us might condemn the people in our lives whose beliefs or actions don’t align with our own. The difference, I think, between those who engage with repair and who don’t is the difference between connection vs. isolation, between reconciliation vs. alienation.

Many memoirs I’ve read over the years have centered on stories, as in Free, that center seeking repair, mending, finding meaning in closure. I’d love to hear your insights on this if you’re an author whose written such a story, or who’s writing one, or of your effort toward repair—which by extension, as Amanda Knox knows, is an effort toward freedom.

Brooke, this was a beautiful post. I loved how you extend your heart to people you disagree with and how you publicly modeled apology and repair. (And then do it again by retelling the story here).

I've been writing about estrangement and reconciliation for more than twenty years now, and have published two books on the subject, yet I still struggle with it in my day to day life, even in my own home. It is an ongoing challenge for me to keep an open heart when I'm hurt and to apologize. It is one of my ongoing spiritual practices, learning to apologize with generosity and no excuses attached.

In particular, I wanted to highlight this line:

"We have so few models of repair in our society right now. Our administration’s symbol of strength and change is a literal chainsaw. It’s hard to imagine something being in deeper contrast to kintsugi than that."

Also, what a great book review--you sold me on reading Jen Knox's book, so thank you for that!

P.S. I have kintsugi woven into the cover of my memoir, too, though many people don't recognize it for what it is. I always love when they do. It was the last element to be added to the design, and I'm so glad it was!

I so deeply appreciated this post. I am one such author, in that I have written a memoir that addresses these themes. Here is where I've landed: I think the work of forgiveness and repair depends on the level of wrongdoing. When it comes to catastrophic wrongdoing, that has, say, lifelong consequences, the process of forgiveness is lifelong, and depending on whether the person who has done the wrongdoing is alive or not, I would even go so far as to say that the work of repair is lifelong, as well. None of this is to say that you can't forgive someone and still decide to end the relationship, just to say that to forgive and stay *in* relationship (which this post addresses), often requires some degree of ongoing repair work, just as the forgiveness work is ongoing. Here is something else: I think we have far greater capacity to forgive all degree of harms than we, as a society, understand, but it's up to us to do the work to reclaim our shared humanity, which is needed if we are going to stay in relationship with each other. No doubt, all of this requires courage and grace and a healthy dose of distress tolerance. Can we do it? I have hope, but still this remains to be seen. I'm glad Amanda's story is receiving recognition. I was a year behind her at UW and in my first quarter there when everything went down in Italy. I also hope other (non-celebrity) memoirs of forgiveness and humanizing others can also make their way into the world, too.