Structure, Deconstructed

Popular Memoir Structures Explained, with Examples

Starting tomorrow, I’ll be co-teaching a class with Linda Joy Myers (National Association of Memoir Writers) called The Evolution of Memoir. We’re in a privileged position with our biannual spring and fall classes to consider topics within our beloved genre of memoir that inspire us, and also make us think and learn and expand our own understanding of what’s possible.

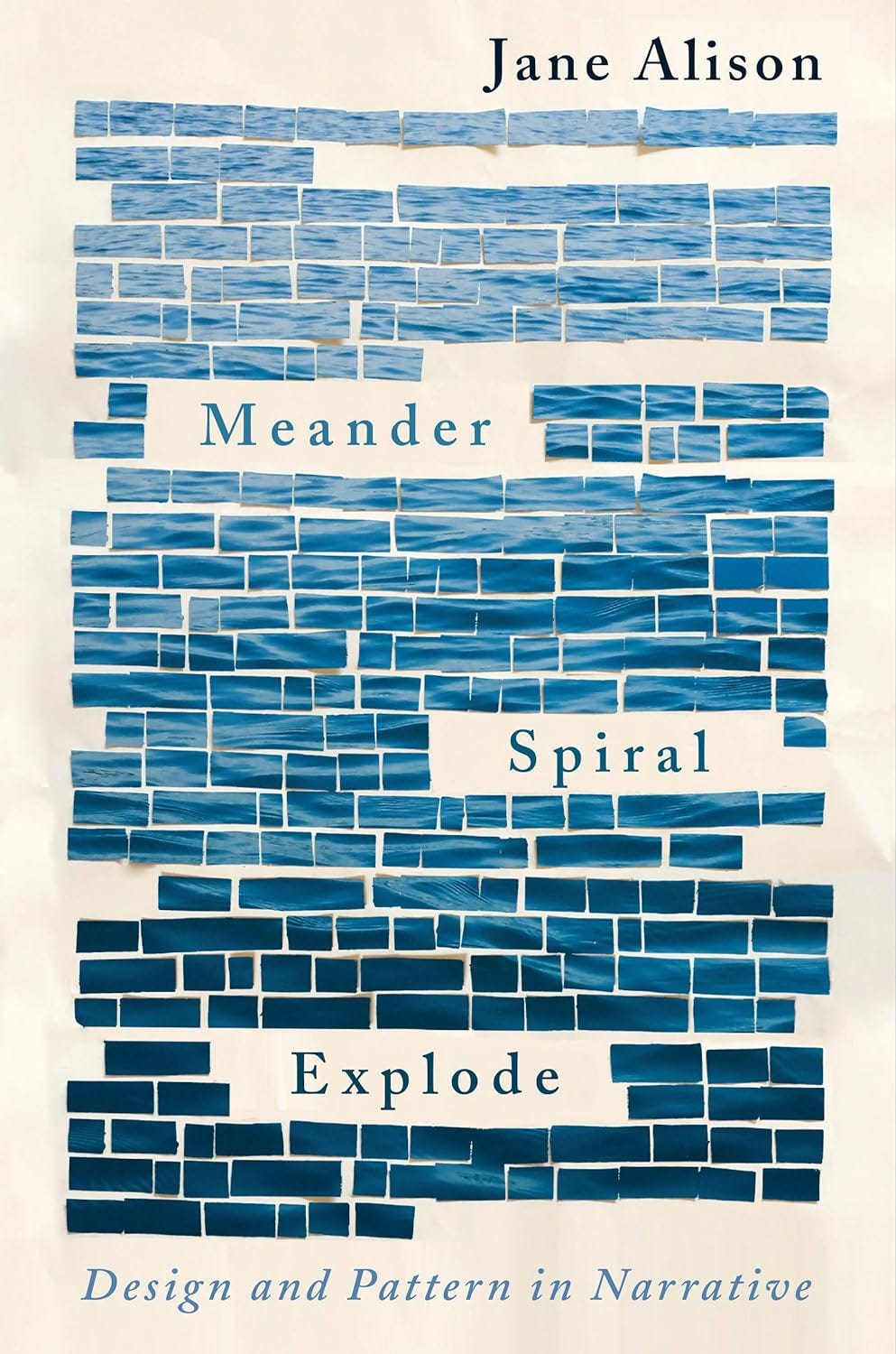

Case in point, teaching this class led me to finally read Jane Alison’s Meander, Spiral, Explode, which I’ve had on my shelf for over a year, on my reading list even longer. It’s a true delight of a book that asks writers to consider how they approach narrative structure, which she frames as design and pattern. Linda Joy and I teach memoir structure in our six-month class and elsewhere, so in rooting around for more language for our four-week class, I decided it was past time to read this book.

If you’re a writer (aspiring, toiling, published, returning, revising), push it to the top of your queue. I’m sad for myself that I waited this long. It’s geared toward novelists, but its application to memoir is clear, and reading a book like this is a reminder of how much memoirists can learn from studying fiction (form and craft), and also that there are many ways to think about and consider structure. Teachers are just trying to put language around things to help students think in ways that support creativity and form. The writer’s job is to sort out for themselves what’s helpful and what doesn’t resonate—and then to carry on.

In Meander, Spiral, Explode, Alison identifies nature patterns—waves, spirals, fractals, cells—and applies them to narrative forms. She also speaks to her ennui—or worse—with the traditional story arc. She writes “. . . I’m bothered again and again that so many smart young writers feel obligated to follow it. It wasn’t a given as Western fiction crawled to life, but gradually became convention, with writers resisting it often.”

When it comes to resisting convention, I’d argue one first must know the convention, then disrupt it with intention. When I interviewed Abigail Thomas on my podcast a few years ago, I knew I wanted to talk to her about breaking the rules because she does that so well. In my memoir classes, I teach foundational principles of memoir because breaking the rules and defying convention is only exciting and satisfying for readers when the writer does so masterfully. I’ve read lots of manuscripts over the years where writers may think they’re breaking the rules, but the reading experience feels more like being in a car with a driver who’s let go of the steering wheel. In other words, not fun.

I’m inspired by Alison’s ideas around structure, and it’s cool to see where her nature patterns overlap with the structures Linda Joy and I already teach, which include:

Linear

A story that takes us chronologically from Point A to Point B, often used in coming-of-age stories, but not exclusively. A linear narrative does (often) follow the traditional story arc that Alison suggests we disrupt. There are plenty of beautiful linear memoirs, however, including: The Glass Castle, by Jeanette Walls; Heavy, by Kiese Laymon; Angela’s Ashes, by Frank McCourt; Autobiography of a Face, by Lucy Greeley. I often suggest, too, that new writers write their memoirs linearly—again to learn the form before trying to break it.

Framed

A story with a linear throughline (Point A to Point B) inside a larger container of a story that uses flashback and memory sequences. Here, I like to use the visual of a hallway, in which the hall is your front story (which could span three months, a year, three years). Along your hallway are myriad doors and windows that lead you to your past. Open any one of them to your backstory. Explore as much as you want, but always come back to your hallway. Examples of framed memoirs include: Wild, by Cheryl Strayed; Inheritance, by Dani Shapiro; and The Memory Palace, by Mira Bartok.

Associative

A story that follows the thread of the writer’s associations. This aligns with Jane Alison’s “meander,” about which she writes: “picture a river curving and kinking, a snake in motion, a snail’s silver trail.” These visuals imply propulsion forward on a consecutive journey, however, where associative bumps and jumps, falls back and scurries forward. So maybe it better aligns with Alison’s “fractal,” which we teach as “fragmented.” Nevertheless, I use the visual of stepping stones because associative encourages a process by which you take the next intuitive step. Another image I like is the old-fashioned brainstorm with your story in the center bubble, hubs of ideas jutting from a central idea. Here, writers may be time traveler, musers, and philosophers. Examples are: Maggie Nelson’s Bluets; Imani Perry’s Breathe; Linda Joy Myers’s Song of the Plains.

Fragmented

What Alison calls a “fractal,” which she describes as a story branching out from a core or a seed. I like this visual because it speaks to the importance of a fragmented story having that core in the first place. Fragmented does not suggest a chaotic structure; rather, it’s a kaleidoscope from which you take in the story bit by bit from different angles as the writer pieces together a satisfying whole. Fragmented narratives are among my favorites, as long as the writer doesn’t lose me. Much like in the associative structure, the writer can time travel, making it all the more important that they be a good guide on the journey. This structure is becoming ever more popular in memoir, and three of memoirs we’ll be using as examples in The Evolution of Memoir fall into this container: Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House; Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful; Abigail Thomas’s What Comes Next and How to Like It.

Braided

A story with two alternating narratives—a front story and a backstory. We teach that writers who feel they have two competing timelines—usually a coming-of-age story and an adult story—can be well served by the braided narrative. This is a structure mirrored in fiction with stories that have alternating points of view. In memoir, the points of view just happen to be the same person/narrator at different eras of their lives. A nonconventional braided memoir is James McBride’s The Color of Water. A nonfiction book worth studying for the braided structure is Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. I recommend Melissa Cistaro’s Pieces of My Mother and Susan Morris’s The Sensitive One as beautiful examples of conventional braided stories.

Circular

The circular narrative mirrors Jane Alison’s “spiral,” which, she writes, “might move around and around with a system of rhythmic repetitions, yet it advances, deepening into the past, perhaps, or rising into the future.” The circular narrative usually circles something the writer wants or needs us to look at again and again. There’s an excavative quality with the circle, a coming back to again and again, spiraling back after having left to explore things that offer more context to the story. Examples include Mary Karr’s The Liars’ Club; Glennon Doyle’s Love Warrior; Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous.

Alison writes in Meander, Spiral, Explode: “This way of seeing structure in narrative might seem reductive; that’s partly my point.” I would argue that any way of trying to teach, see, and understand structure is reductive, and I put this forward here as an intentional qualification.

I remember meeting Cheryl Strayed in San Miguel de Allende years ago when she was keynoting at their annual writers’ conference. I excitedly approached her to ask her about her framed structure, to which she replied she had no idea, basically, what I was talking about. This hadn’t been how she approached Wild, hadn’t been her own understanding of her structure. And yet, to me, Wild is a near perfect example of a framed memoir. When I interviewed Kiese Laymon on my podcast and listened to him talk about his work, I was mesmerized by his articulation of what his book is, and the many considerations behind the meaning of “heavy.” So here, placing his book inside the linear bucket doesn’t suggest there’s anything simplistic about that, or that other layers of craft aren’t happening.

Form is about finding the container for your work. Alison quotes Ronald Sukenick, who said about form, “Form is your footprints in the sand when you look back.”

Structure matters insofar as it’s a container that holds your story. Stories can be hyperstructured or loosely structured; writers can be more or less obsessed with structure; we might have different words, language, or understanding of what structure is in the first place, and which books meet which definitions of that understanding. To me, structure feels like the net below our acrobatics. When we do our best writing, we’re soaring like trapeze artists, testing our capacities, practicing our art. It’s a little bit reckless at times, which is why structure and form so often feel like a balm—something to lean into, to steady us, to catch us when we fall.

Consider joining me and Linda Joy for The Evolution of Memoir. We’d love to spend these next four weeks with you.

4 Mondays:

March 4, March 11, March 18, March 24

1-hour class (3-4pm PT | 6-7pm ET) followed by

1 hour of generative writing (4-5pm PT | 7-8pm ET)

Cost: $299

In The Evolution of Memoir, we’ve chosen six books that break memoir convention to center our examples on—Maggie Nelson’s Bluets; Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House; Imani Perry’s Breathe; Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful; Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous; and Abigail Thomas’s What Comes Next and How to Like It. It’s not necessary to have read these books before class starts.

I'm trying to begin a non-traditional memoir. Meander, Spiral, Explode has been in my stack too, since I heard about it recently on another webinar. Your post got it from stack to hand today. Maggie Smith's book first got me thinking that what I want to do was not ridiculous. Your interview with her—along with Grant Faulkner—was so helpful. Thank you for a terrific post, Brooke. I too, will keep it close by when my project confuses me, again.

Many thanks to you Brooke for this thorough deconstruction of structure. I feel more confident that I can read as a writer and recognize different structures due to the books you highlight and offer as examples.