Memoir Is a Mirror

What the blowback over Liz Gilbert's new book tells us about ourselves

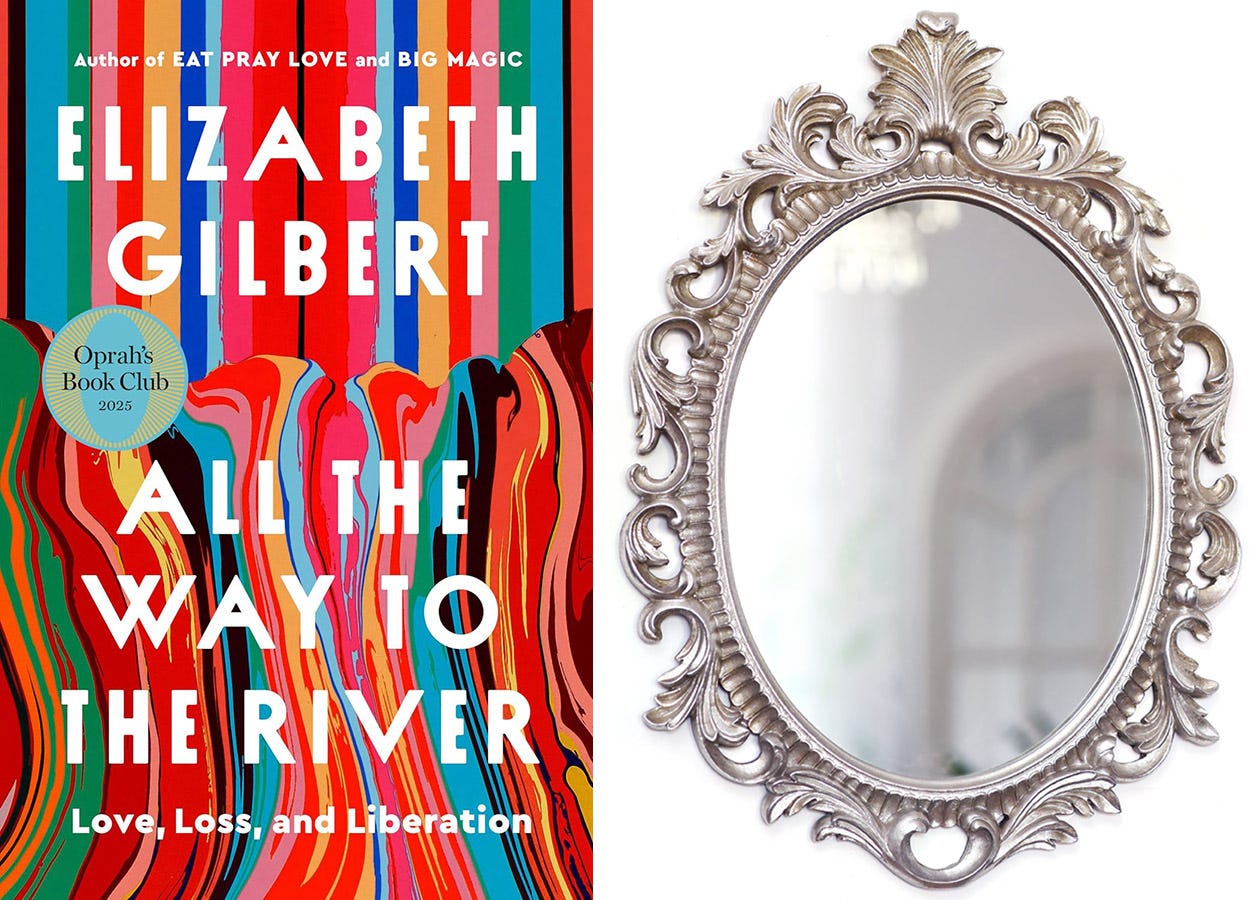

On a single day last month, before the book was even out, Elizabeth Gilbert’s memoir, All the Way to the River, turned into the most hotly anticipated and most reviled new release of the season.

This happened with the publication of an excerpt on August 30 in The Guardian, in which Liz writes about wanting to murder her late partner, Rayya Elias. She writes that their apartment was full of cocaine—and whiskey and several bottles of morphine and trazodone and Xanax and a stack of fentanyl patches and a cluster of empty beer bottles. I’m not gonna lie. I was bug-eyed when I read the passage aloud to my wife. These were two well-off women in their fifties, after all, one of whom is a world-famous author with a bit of a goodie-two-shoes reputation. So yeah, it was a lot.

But then the online firestorm started, and that was a lot, too. I racked my mind to think of a comparable fallout/blowout in memoir and the only one that comes close is Kathryn Harrison’s The Kiss (1997), which was about the author’s sexual relationship with her estranged father. You might ask yourself what is the single topic other than having a sexual relationship with one’s estranged father that might elicit as much or more public ire and outrage? Contemplated murder of one’s loved one. Check.

We can’t look at the current pushback on Liz Gilbert without considering Eat, Pray, Love and what that book did to her. It wasn’t just a memoir, it was a cultural phenomenon. Readers (mostly white, well-off women in their thirties, forties, and fifties) treated it as a blueprint for how to have a better life, and Liz became the designated leader of a particular kind of self-improvement movement. It’s interesting that Liz gave a 2009 TED talk called “Your Elusive Creative Genius” in which she fretted over the burden of expectation. Public scrutiny was already looming, and she knew that everything she ever wrote following Eat, Pray, Love would be measured against the singularity of that success. So, it was no surprise that she got a fair share of backlash for her second memoir, Committed. Readers called her self-indulgent, accused her of treading well-worn territory and thinking she was so special.

Dear readers, newsflash. Memoir is self-indulgent in the same way taking care of yourself is selfish. If you don’t like reading books about people’s personal lives, and how they makes sense of their experience, memoir is not your genre.

So many indignant comments littered my social media feeds this week from people who asserted that they would not read this book. The usual rounds of diagnoses and name-calling followed: narcissistic, hysterical, unstable, exploitative, manic, problematic, an asshole.

Witness me as bug-eyed watching all this unfold as I was reading The Guardian excerpt. How we love to knock people down. How self-satisfied we are when we get to pathologize someone who’s soared just a little too high.

On the merits of the book

I read the book over three days and here are my thoughts.

It achieves what a memoir should in that it made me think more deeply about the nature of its primary subject: addiction. It made me ask questions about my own life. It helped me to consider relationships I’ve had with addicts. My ex-wife’s addictions played a role in the demise of our relationship. My current wife is an alcoholic many many years sober, but she still works the program, and much of Liz’s language was familiar to me from being in partnership with someone who walks the talk. I thought Liz handled these parts with care, and with the unfolding honesty of someone who goes into recovery rooms kicking and screaming and who comes out the other side humbled and changed.

Liz is a beautiful writer. She’s deeply insightful. There are passages that made me cry. It was hardly the worst seven or eight hours I’ve ever spent. I got a lot out of the book.

Also, it’s not perfect.

I could have done without the channeling of Rayya, and especially of Rayya’s mother. I strongly dislike it when memoirists embody the no-longer-living. I like it even less when the dead person’s dialogue is recreated/invented. I like woo-woo, but I like my woo-woo measured. So some of the past life stuff—that Liz and Rayya’s story was written in the cosmos a bazillion years ago, or that they’d loved or murdered each other in previous lives—really didn’t do it for me.

This week on the Memoir Nation podcast, our guest is Roxane Gay (out on Monday), and imagine my thrill when she got into it on Liz’s memoir with us. Her take—that the poetry and the illustrations were “ill-advised”—was my take, too. If a memoirist came to me at She Writes Press and showed me her elementary artwork and conversations-with-God poetry, I would say: No, we’re not doing that.

spoke to this in her Washington Post review, writing that the book would be so much better absent its “fatty connective tissue: didactic passages on addiction, 12-step wisdom, women’s history, trauma theory, and captioned scribbles and poems, all of which probably would have been excised if their author lacked millions of presold fans.” Correct, which is why you should never use the excuse that Liz Gilbert did it so you should be able to, too, with future prospective publishers.Liz has earned her right to write the book she wants to write. And I have no doubt this book is exactly as she wants it to be—a tribute to Rayya and a genuine effort to support other codependents and sex and love addicts. I am not a codependent. I am not a sex or love addict. Still, I love books about psychological dynamics. I appreciate reading books that help me to better understand human nature, which is one of the reasons I love memoir. I saw in Liz’s portrayal of codependents and sex and love addicts some of my friends. That she gave me a framework to better understand people I love is a real gift.

And, Liz was never not going to write this book. I relate. I am going to (someday) finish my memoir about my journey with my ex because our story will never let me go. When you have something beautiful that gets ground to a pulp by circumstances that are out of your control, you rail against the universe. You have to find your way back to equilibrium, back to sanity, or it will pull you under. Many people do that through writing their memoirs. Liz is no different. She’s just far more skilled at it than most, and she’s much much more famous than most.

And so, here we are.

On the public blowback

I’ve spent a career witnessing women writers get raked over the coals for daring to tell their truths. The subjects for which women regularly get raked include: choices around motherhood; mental health challenges; speaking ill of one’s parents; being overtly or overly sexual; writing about sexual or gender identity; victimhood in all its permutations; addiction in any form; body and body image struggles—to name a few.

A story.

I met Liz Gilbert at a dinner during Oprah’s 2014 “The Life You Want” Tour, where both Liz and Mark Nepo were speakers. I was there as Mark’s guest, and Liz and I sat across the table from one another. What stuck with me, besides her inherent kindness and genuine interest in the other guests at the table, was something she said about Eat, Pray, Love. This is paraphrasing, but she said that on the heels of publishing Eat, Pray, Love, she had a profound realization that it was no longer her story. It became everyone’s story, she said, and she’d come to understand that she had no say over what other people wanted or needed it to be.

That’s come to mind as I’ve read the reactions to All the Way to the River, which are really reactions to Liz. People project onto memoir (and therefore onto memoirists). If you relate to parts of the story, it can be either profoundly helpful or profoundly irritating. If a memoir hits too close to home, you may not like it for that very reason.

In my online circles, the most amount of vitriol has come from people who preface their negative reactions by sharing their own stories. They were caretakers to the ill and the dying. They are addicts. They have addicts in their family. They would have handled things differently than Liz, and they don’t like her for that. Okay, then. Memoir is a mirror, so if you feel upset or angered in any way by Liz herself and the choices she made, just notice.

Liz is a master at naming things. She is excessively self-aware. In many ways this book is about always wanting more and never feeling like enough. It’s an ugly thing to admit, always wanting more and never feeling like enough, and yet, isn’t this the cultural inheritance of an entire generation of American women who were born into privilege, who came of age in the era of Reality TV, and who have spent our formative adult years dealing with the pressures and visibility of social media? We want we want we want . . . something. To be seen. To be fulfilled. To have an extraordinary life. One gift this book offers up is a singular truth: that even when you get it all, it’s still not enough. The book is an exploration of looking within, and the power of understanding and naming the external forces that hold us hostage to these wants.

On the fine point of contemplating murder, which is a pretty terrible thing to confess, I will say that had I been Liz’s editor, I wouldn’t have suggested she cut the scene. It’s her rock bottom. It’s the moment when she no longer recognizes herself. And it’s signature Liz—honest to a fault.

Many years after The Kiss came out and many years after Kathryn Harrison was publicly shamed in all the expected ways, she and her story became part of a broader conversation about memoir, trauma, and women’s right to tell difficult stories. By the 2010s, critics were revisiting The Kiss (its 2011 edition has an afterword by Jane Smiley), calling it groundbreaking. It was praised as unflinchingly honest and transgressively courageous, a bold exploration of taboo.

I’m singularly obsessed with memoir for its window into the psyche, and that obsession extends into these cultural moments of fallout, too. Memoir shows us the full range of human experience and expression. The writing of it and the receiving of it tell us so much about ourselves. When we understand other people’s drives and motivations, it can help us make sense of our own. If we’re honest about why we love and/or hate what we read, we’ll discover it’s because we’re making it about ourselves. Memoir, by definition, is about the self, so when we rush to call it self-indulgent, it says more about our own discomfort with vulnerability, confession, or taboo subjects than about the writer’s intent.

Does the writer’s intent matter? I think it does, yes. I also think that memoirists are on the front line of cultural change, pushing and fighting to bring to light topics that are oftentimes challenging and ugly in their truths. So, to the memoirists out there, keep going. Fallout may or may not be lingering out there for you. Very few of us run the risk of triggering the kind of outrage Liz Gilbert does just for doing what she does. Still, this is a cultural moment worth paying attention to if you are a writer or a reader of memoir. It’s a once-in-a-decade blowup, and we are a part of this story.

and I recorded a video chat inspired by Roxane Gay, Liz’s new book, and our firm belief that writers need to tell the story they need to write.

This is one of the most enlightening essays I’ve read about memoir in a long time. Thank you!

brooke,

this is a stellar post! A piece for the times. you have captured the jagged edges of what it means to be a woman in our society. But it’s more. Everyone needs to look in that mirror before they open their mouths, before they share the words they tap into their computer. I so appreciate what I learn about Liz, readers, memoir, and you.

this passage rings out, demanding we listen:

I’ve spent a career witnessing women writers get raked over the coals for daring to tell their truths. The subjects for which women regularly get raked include: choices around motherhood; mental health challenges; speaking ill of one’s parents; being overtly or overly sexual; writing about sexual or gender identity; victimhood in all its permutations; addiction in any form; body and body image struggles—to name a few.

thank you. i’m waiting patiently for your memoir 💕