It's Not Okay to Say Things Are Hard for White Writers Right Now, but It's Dishonest to Suggest Publishing Hasn't Changed Since 2001

American Fiction deserves the recognition it's getting, but so does the publishing industry for the progress it's making toward racial equity

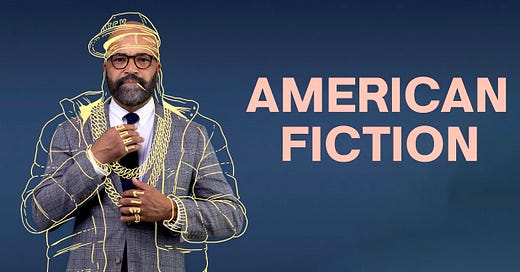

The film American Fiction got quite the nod from the Academy this year. Up for Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Supporting Actor, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Original Score, I imagine we’ll see its team go home with at least three trophies on March 10, maybe more.

I loved the film. It was funny-cringey and offered some well-deserved jabs to the publishing industry, and was smartly treated by its director, Cord Jefferson, as more parody than polemic, which is how the novel upon which it’s based (Percival Everett’s 2001 book, Erasure) is often described.

As an industry watcher, however, the more I’ve thought about the film, the more it’s felt of that earlier era in which Erasure was published, and that publishing itself deserves some credit for its efforts to right some longstanding wrongs. Undoubtedly publishing is still very white. The infrastructure of publishing is slow to change, and people aren’t quick to leave. Undoubtedly it’s still difficult to be a Black writer in America. Black writers feel like they have to cater to the industry, often feel pressured to center race in their work, and #PublishingPaidMe showed us in 2020 that they’re paid far less than their white counterpoints.

Still, things are far better than they were in 2001. Black writers of serious books, and serious works of fiction of the sort that Thelonious “Monk” Ellison writes in the film, are award-winning and celebrated authors with crossover audiences. They’re not few and far between, either. In a December article about American Fiction for the Los Angeles Times, Bonnie Johnson wrote: “BIPOC publishing professionals have worked hard to give voice to more diverse Black stories. . . . The industry has a long way to go, but if Monk’s tossed-off manuscript were to shoot past the ranks of genre standard-bearers and be anointed by the mainstream establishment, a release this year would be competing with hits by James McBride, Zadie Smith, Jamel Brinkley, Victor LaValle, Brandon Taylor, Colson Whitehead, Bryan Washington, and Teju Cole, none writing about thug life or sharecropping — and none recognized by this film.” Let me hasten to add to this list Jesmyn Ward, Tayari Jones, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Jabari Asim, Kiese Laymon, Jacqueline Woodson. We could go on and on and on.

In my 2017 TEDx talk, I spoke about how publishers were quick to qualify that certain books, like books by Black authors and LGBTQ authors, had limited readerships because the default thinking of the industry then was that Black readers read books by Black authors, that queer readers read books by LGBTQ authors. To me, the biggest sea change in publishing in the past four years has been that industry professionals no longer believe this to be true. It’s been proven otherwise, and the result is that previously marginalized writers are being given more latitude to write what they want, and more credence that they can and do reach wider readerships.

But we’re also in a complicated moment because it feels risky to voice aloud that things seem “better” when they’re still bad. This is true in all arenas of progress, however, and if we pretend that things are the same as they were in 2001, we discount the remarkable changes we’ve lived through, and are still living through.

With said progress, too, comes backlash. A more timely movie would have been one in which the movie’s antagonist is calling “reverse racism” on a successful Black writer. In 2022, James Patterson and Joyce Carol Oates, two authors so famous they’re household names, each said aloud what plenty of white writers believe to be true—that no agent or publisher wants to acquire work by middle-age white men right now.

People were quick to condemn Patterson’s and Oates’s comments, pointing out that they’re wrong, first and foremost. That more white writers are still getting published than writers of color. Naysayers pointed to a Penguin Random House audit that showed that White contributors accounted for 76% of books released between 2019 and 2021.

I do not condone what Patterson said—basically that white writers not getting looks or not getting as many opportunities was “another form of racism.” Yikes. But what Oates said is something I’ve heard from a lot of white writers—that “a literary agent told me that he cannot even get editors to read first novels by young white male writers, no matter how good; they are just not interested.”

I know a NYT best-selling white male author in his sixties who in fact can’t sell a manuscript he’s had out on submission for a while. I’ve read it. It’s a great book, but it centers race. Would it have been scooped up ten years ago? Probably. Should it be picked up now? Not necessarily so. Books don’t get published just because they’re good, and I don’t feel badly for this author that now is not the right moment for that book. There’s a sentiment in the industry that white people should take a back seat on writing about race. I don’t think this will last forever, but it’s also ironic or sad or another real indictment on the industry that Black authors speak to feeling pushed to center race in their books while for white writers it’s a hot potato that few publishers will touch. It’s certainly an industry that loves to box people in.

Industries go through ebbs and flows, though, and publishing follows trends and what readers want. Book publishing claims to be the arbiter of our cultural values, but really it’s just a mirror. Publishing gives readers what they want, and we’re in a moment where white writers are not getting the same default consideration they’ve always gotten in the past. That doesn’t mean that white writers are not getting published; of course they are. But to suggest that nothing has changed for white writers is as dishonest as claiming nothing has changed for Black writers. When I open up Publishers Weekly, or look at upcoming conferences, or just generally look around at what books are breaking out in the past few years, many many authors are writers of color. This is something to celebrate. And, like most in-progress cultural change, we haven’t come far enough.

There are more than a few scenes in American Fiction that ring true today—the over-excitement by white publishing professionals for something “fresh” and “authentic” that really just contributes to stereotypes; the professing by white people that it’s time to “listen to” Black people while completely not listening to them and overriding their legitimate concerns; the gross marketing campaigns that capitalize on what’s often referred to as “trauma porn,” or blatant cashing in on white wokeness, characterized by the marketing professional (played by Michael Cyril Creighton) who suggests the film be released to coincide with Juneteenth because “white people will be feeling—let's be honest—a little conscience stricken.”

And, as a person who’s long acquired books, who curates a podcast, who’s deeply involved in programming decisions at this year’s Bay Area Book Festival, who’s celebrating that the Independent Book Publishing Association just appointed its first Black Chairperson, I can say that publishing wants more voices of color everywhere. White professionals in this space get that people of color need to be in the room and that their voices need to be heard. It’s not just lip service; it’s a moral mandate. Is that going to result in white people being awkward allies sometimes? Yes. Are there annoying allies in this space who pat themselves on the back for the work they perceive they’re doing to elevate voices of color? For sure.

As frustrating as it must be for Black writers to hear white writers complain that they’re not at the head of the line anymore, there should be room to talk about all the ways that people get pushed and pulled, prioritized or cast to the side. One of my first Substack pieces was about ageism in publishing. Many people wrote in the comments about their own experiences. It’s just true that the industry is ageist, and we are an ageist society. Now I’m giving voice to the discomfort that’s resulting from the push for racial equity in publishing because that discomfort is real. I don’t think it helps for people to deny that white writers feel like it’s hard for them right now while also acknowledging that Black writers have felt that struggle forever. For this reason, there’s a sense among many, myself included, that it’s okay for white writers to feel that crunch, and to be on their own uphill battle in this journey.

I like seeing the changes publishing has made in these past four years, and I’m an active participant in ensuring that the spaces I’m in (my podcast, the festival) are representative. And so, publishing deserves some credit. The industry is flawed. There’s a lot to cringe at, and there have been countless embarrassing racial missteps, and there are many historical harms that take more than just a few years to atone for. At the same time, the industry is actually doing better. So as much as I loved American Fiction, it seems important to say—we’re currently better than that. And that’s worth, if not celebration, at least a nod of acknowledgment. Let’s keep up the hard work.

Excellent piece. You have such a comfortable style, especially when writing about complicated subjects.

American Fiction was such a brilliant high-wire act and possibly the best film about publishing ever.