Freytag’s Pyramid Wasn’t Made for Memoir

On structure, form, and ways to start your story that don't include an "inciting incident"

Before we get started, Happy Mother’s Day to all the mamas—to those who nurture, tend, support, show up, caretake, mentor, and love. I’m celebrating these life-affirming connections with you today.

I’m wrapping up a four-week class with Linda Joy Myers on Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful. Last week, a student brought up an excellent question about narrative arc. A friend of hers, she shared, had a hard time getting through You Could Make This Place Beautiful because, according to this friend, there’s no narrative arc.

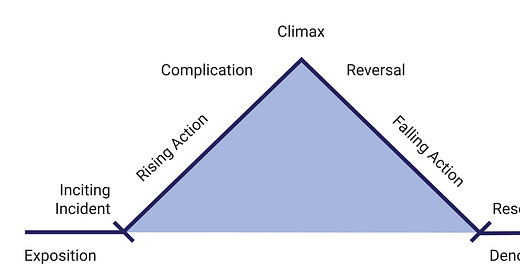

Of course, You Could Make This Place Beautiful has a narrative arc. What it doesn’t have, however, is a linear structure, nor does it adhere to the only story structure any of us is taught in primary school, which is called Freytag’s Pyramid:

It seems appropriate to write about Freytag’s Pyramid on this day when we celebrate a holiday like Mother’s Day, and on this week when the Catholic world is ushering in a new pope. Humans love tradition. We love to worship at the altar of “how things are done.” Historically, people who bucked tradition were heretics. Artists who break the mold are rarely lauded for those efforts in real time. A Complete Unknown, the Bob Dylan movie, is exemplar of this very human impulse to lose our minds when someone breaks the mold. Dylan wrote some of the most-loved folk songs of all times, but then he wanted to do new things, the people who’d assigned themselves to be the protectors and boundary-drawers of folk music were none too happy.

It's similar in memoir. People’s minds are either expanding or exploding right now because the genre is bursting open with experimentation and new forms. I hope you’re in the mind-expanding camp because it’s a lot more interesting and fun over here. Writers are blowing up the boxes of memoir—and those who cling to Freytag’s Pyramid as if it’s the only way to write a story remind me a lot of those people who wanted to insist that Dylan do folk the way folk was supposed to be done!

Here’s what needs to be said about Freytag’s Pyramid. Gustav Freytag was born in 1816. He was a novelist and playwright. He was a problematic figure and the pyramid is as often criticized as it is defended, but still . . . two hundred years have passed, and the heyday of memoir started in the 1990s. Whether or not Freytag was personally policing storytellers to adhere to his mandate of how to tell a story, or whether his pyramid was simply adopted by the powers that be as the gold standard, a rule by which to adhere, it doesn’t really matter for twenty-first-century storytellers. Importantly, there are so many models out there for how to do it otherwise, and how to break free.

In Meander, Spiral, Explode, Jane Alison writes, “For centuries we've been told there's only one way to tell a story . . . But what if stories don't arc? What if they meander, spiral, explode?”

Precisely. Furthermore, I have worked with countless memoirists who simply don’t like the classic linear arc. Their story doesn’t fit inside its perfect rising tension/climax/denouement. Or, importantly, they’re bored or stuck within its constrictive confines. We call this being straightjacketed, and you will squeeze the life out of your story if you keep wrestling inside of a form that doesn’t want to be.

Memoirs also don’t tend flow from a single moment, but rather they circle experiences, many of which last for years. These are just a few of the types of stories that don’t easily lend themselves to a particular inciting incident:

• the child-parent relationship

• drug or alcohol addiction

• divorce

• mental illness

• abuse/surviving it

But when you have a story that’s not incident-driven, questions arise of how and where to start, if not with a moment? Well, you can still start with a moment, but it doesn’t have to be explosive action. Your moment can instead paint a picture, or set context, or orient the reader as to what to expect.

Here are a few other ways to start:

• Character-driven—start with a scene that’s meant to set up a person or a particular dynamic (as seen in J.R. Moehringer’s The Tender Bar, or Jeannette Walls’s The Glass Castle, or Ann Patchett’s Truth & Beauty)

• Setting-driven—start by painting a picture (as seen in Jill Ker Conway’s The Road from Coorain; or Sarah M. Broom’s The Yellow House)

• Subject- or meaning-driven—start with your themes (as seen in Heavy, by Kiese Laymon; or Blow Your House Down, by Gina Frangello)

• Context-setting—start with something that shows how things were before they changed (as seen in Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior; or Mary Karr’s The Liars’ Club; or Piper Kerman’s Orange Is the New Black)

• Orientation—start with orienting the reader as to what to expect (as in Maggie Smith’s You Could Make This Place Beautiful, or Joan Didion's The Year of Magical Thinking)

Some of these above-mentioned memoirs above are in fact linear narratives, and to be clear—it’s a structure worth loving and championing. If your book works as a linear narrative and works for you, wonderful. But increasingly I think linear narratives are best for stories that span shorter periods—a year, a couple or three years. If the story you’re writing spans a decade, two decades, a whole life, other structures will undoubtedly feel more freeing.

As hard as things are right now—on the world stage, in politics, socially, culturally—within the world of storytelling, there’s never been more permission. I just finished the book by the same name, Permission, by Elissa Altman. She’s coming up on the Memoir Nation podcast soon (of course!) because she’s tapping into a zeitgeist that I’ve been riding for a while now. It goes something like this: Tell your story. Tell it the way you want to tell it. Don’t get caught up by what other people think they know is best for you. Check in with your heart often. Be discerning, but cultivate supportive voices. Keep writing. Your story matters.

Brooke, this is such a good insight. "But increasingly I think linear narratives are best for stories that span shorter periods—a year, a couple or three years. If the story you’re writing spans a decade, two decades, a whole life, other structures will undoubtedly feel more freeing." I hadn't thought of it before, but of course.

Also, Elissa Altman! I wish I had read her memoir "Motherland" before I wrote Deep Memoir--so much to say about that memoir! She's a huge missing piece in my reading list in the end. Glad you'll have her on the podcast.

So true. Each memoir is its own unique story (within general types) and needs an opening that suits it. I was worried about opening my sailing memoir, mostly set in 1990, in the present day, but when I suggested starting with chapter three, my editor, my advance readers, and my publisher all said no!